This document is relevant for: Inf2, Trn1, Trn2, Trn3

Activation Memory Reduction#

There are three major contributors to high device memory utilization: Parameters, Optimizer states and Activation Memory. To reduce the size of parameter/optimizer states memory, one can use parallelism techniques like Tensor-parallelism, Pipeline-paralleism or Zero1. However, as the hidden size and sequence length increases, the size of the activation memory keeps growing linearly with hidden size and quadraticly with sequence length.

The total activation memory without any parallelism comes to about:

where,

a: Number of attention heads

b: microbatch size

h: hidden dimension size

s: sequence length

When we use tensor-parallelism, it not only helps to reduce the parameter and optimizer states size on each device, but it also helps to reduce the activation memory. For a transformer model, where we apply the tensor-parallel sharding on the attention block (more info here), the activation memory within the attention block also drops by a factor of tensor-parallel degree (t). However, since the layernorms and dropouts (which are outside these attention blocks) are not parallelised and they are replicated on each device. These layernorms and dropouts are computationally inexpensive, however, they increase the overall activation memory on each device. Moreover, since we only parallelize within the attention block or within the MLP block (h -> 4h projection), the inputs to the QKV multiplies and the MLP are still unsharded. This overall adds to about 10sbh of total activation memory. To reduce this activation memory, one can use 2 methods:

Sequence Parallelism#

Sequence-Parallelism was proposed by Shenggui and et.al . The authors propose to parallelize the compute along all the sequence dimension in an attempt the reduce increasing the memory pressure due to high sequence-lengths. Sequence-parallelism can be combined with tensor-parallelism to reduce the activation memory pressure due to increasing sequence-lengths.

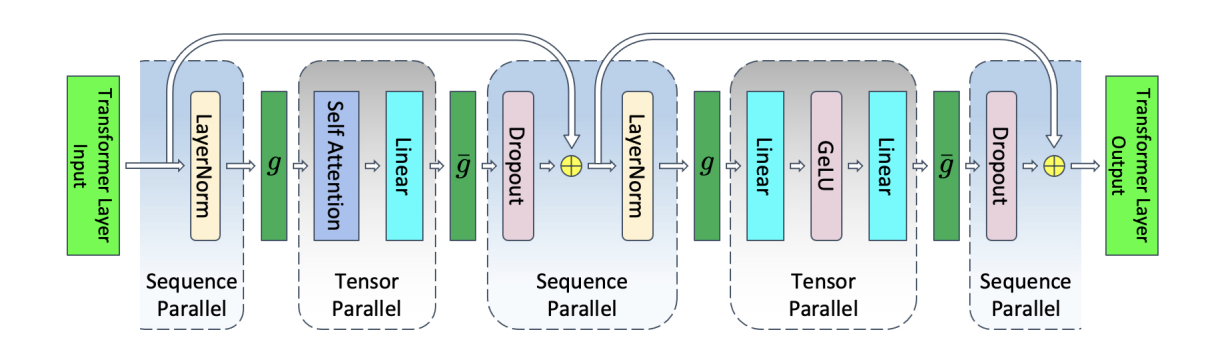

Tensor-parallelism parallelizes the parts of the transformer which are computationally heavy, however, it leaves the layer-norms, dropouts and some MLP block intact. The activation memory for this block adds up to a factor of 10sbh. Vijay Korthikanti et.al noticed that the compute in the non-tensor parallel region is independent in the sequence dimension. This property can be leveraged to shard the compute along the sequence dimension. The main advantage of sharding these non-tensor parallel block is reducing the activation memory. We can use the same tensor-parallel degree to partition, thereby reducing the overall activation memory by a factor of t. However, this partitioning comes at a cost. Since we are partitionining the non-tensor parallel region along sequence dimnesion, we have to collect the activations before we feed to the tensor-parallel block. This requires an introduction of all-gather collective operation which would gather the activations along the sequence dimension. Similarly, after the tensor-parallel block, since we would have to split the activations along the sequence dimension and distribute among the devices. Since, the tensor-parallel block in the transformer module already uses an all-reduce (Row-parallel linear layer used for MLP), we can replace the all-reduce operation with a reduce-scatter operation.

Ref: Reducing Activation Recomputation in Large Transformer Models

In the figure, g is all-gather operation and g¯ is the reduce-scatter operation. g and g¯ are conjugates and in the backward pass, g¯ becomes an all-gather operation and g becomes the reduce-scatter operation. At first glance, it appears that sequence-parallelism when combined with tensor-parallelism introduces an extra communication operation, however, in a ring all-reduce, the op is broken down into all-gather and reduce-scatter. Hence, the bandwidth required for sequence-parallelism is same as tensor-parallelism only. Hence, we are not losing out on compute but end up saving the activation memory per device. The final activation memory when sequence-parallelism is combined with tensor-parallelism:

Activation Recomputation#

The total required memory in the above equation can still be high as we increase the sequence length and hidden size. We would have to keep increasing the tensor-parallel degree to accommodate this requirement. Increasing the tensor-parallel degree might soon start producing diminishing returns as the model would start becoming bandwidth bottlenecked because of the extra collective communication operations. Activation recomputation can help to alleviate this problem. In this method, we recompute a part of the forward pass during the backward pass, thereby avoiding the need to save the activations during the forward pass. Activation recomputation is a trade-off between duplicate computation vs memory. It allows you to save on memory at the cost of extra recompute. This trade-off becomes valuable when we can fit larger models at the expense of recomputing forward pass activations.

Ideally one can recompute the entire forward pass, there by resulting in an activation memory of 2sbh per transformer layer. This method is called Full-activation checkpointing. This memory can further go down by a factor of t if we use tensor-parallelism. In the activation memory equation, we have a quadratic term of 5abs^2. As the sequence length, this term will grow at a much faster rate. This quadratic term comes from the softmax computation. Vijay Korthikanti et.al propose Selective activation checkpointing where they only recompute the softmax and attention computation and thereby avoid saving the activations coming from softmax and attention computation. This completely gets rid of the quadratic term and brings down the activation memory per layer to 34sbh/t. The LLama-7B example in this tutorial used selective activation checkpointing.

This document is relevant for: Inf2, Trn1, Trn2, Trn3