NKI Direct Allocation Developer Guide#

In this document, we will discuss how to perform direct allocation in NeuronCore on-chip memory (SBUF and PSUM) correctly and efficiently to improve NKI kernel performance. This document is organized into five sections:

Background: NKI Tensors Semantics#

As discussed in NKI programming model, a multi-dimensional NKI Tensor in SBUF/PSUM must have a dimension mapped to the partition (P) dimension of the physical memory, labeled using nl.par_dim. We also define any NKI Tensor with the first dimension as the partition dimension is considered a NKI Tile, which is the data type that NKI compute APIs operate on. The remaining dimensions after the partition dimension in a NKI Tile are considered free (F) dimensions. The free dimensions describe how data is organized within each SBUF/PSUM partition.

To introduce NKI allocation API, let’s define the block (B) dimension as any dimension before the partition dimension in a

NKI Tensor. Therefore, a NKI Tensor has three types of dimensions: (B, P, F). Note, a NKI Tensor can have one or more

dimensions in both B and F, but there can only be one dimension in P due to Neuron ISA requirements.

The block dimension effectively describes how many (P, F) NKI Tiles the tensor has, which commonly corresponds to how many

NKI API compute API invocations we need to process the entire tensor.

As an example, we can declare a NKI Tensor in SBUF as follows:

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((16, nl.par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16, buffer=nl.sbuf)

for i_block in nl.affine_range(16):

nki_tensor[i_block, :, :] = nl.load(...)

... = nl.exp(nki_tensor[i_block, :, :])

Here, nki_tensor has a block dimension of 16, and we use it as an intermediate SBUF tensor for loading data

from device memory and feeding inputs to the exponential operator. The different tiles in nki_tensor are processed

by different iterations of a loop constructed with nl.affine_range(...), indicating no loop-carried dependency

across iterations.

In fact, the block dimension of nki_tensor as defined above is only considered logical in NKI.

Neuron Compiler inspects the above code and uses a heuristic-driven allocator to decide how many physical tiles

are allocated to each tensor. The key performance goal of the allocator is to achieve instruction parallelism

across different engines in NeuronCore while minimizing memory usage in the on-chip memory.

Let’s first consider the case where nki_tensor has only one physical tile, T, allocated in SBUF. The different loop

iterations will end up completely serialized:

i_block = 0

1. nl.load(nki_tensor[0, :, :]) => write ``T``

2. nl.exp(nki_tensor[0, :, :]) => read ``T``

i_block = 1

3. nl.load(nki_tensor[1, :, :]) => write ``T``

4. nl.exp(nki_tensor[1, :, :]) => read ``T``

...

Here, we say only one logical tile in nki_tensor is alive at a time, because there is only one physical tile as the

backing storage for nki_tensor. However, in NeuronCore, nl.load and nl.exp are executed using two independent

resources: DMA Engine and Scalar Engine. In this serialized execution, there is no instruction parallelism achieved

between these engines.

An obvious improvement is to adopt “double buffering”, by allocating two physical tiles for nki_tensor,

T0 and T1. Now, the execution enables much better computation and data movement overlapping:

i_block = 0

1. nl.load(nki_tensor[0, :, :]) => write ``T0``

i_block = 0 & 1

2. nl.load(nki_tensor[1, :, :]) => write ``T1`` | nl.exp(nki_tensor[0, :, :]) => read ``T0``

i_block = 1 & 2

3. nl.load(nki_tensor[1, :, :]) => write ``T0`` | nl.exp(nki_tensor[1, :, :]) => read ``T1``

...

Here, we reuse, or rotate, the same physical tiles across the loop iterations. No physical tile is being read from and written to in the same time step, while the DMA and Scalar Engines can operate in parallel. Besides DMA and Scalar Engines, NeuronCore also consists of Tensor, Vector, Gpsimd Engines that can execute instructions in parallel.

Given the amount of parallelism available in hardware and the complex parallel programs seen in common machine learning workloads, the heuristic-based memory allocator in Neuron Compiler may not yield the optimal allocation decisions. Bad allocation decisions typically lead to sub-optimal engine parallelism and/or on-chip memory over-subscription causing excessive spills of intermediate data to device memory. With NKI direct allocation API, programmers can now bypass the compiler allocator and take full control of memory allocation in SBUF/PSUM for NKI Tensors.

Direct Allocation API#

This section will go over the SBUF allocation in detail, including ncc.sbuf.alloc() API that provides the most

flexibility for tensor allocation and ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc() API that provides ease-of-use using

a modulo allocation strategy. Both of these APIs can be used to replace the automatic allocated buffer type

buffer=nl.sbuf when declaring a NKI tensor:

# Automatic allocation

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((16, nl.par_dim(128), 512), ..., buffer=ncc.sbuf.auto_alloc())

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((16, nl.par_dim(128), 512), ..., buffer=nl.sbuf) # alias of auto_alloc

# Direct allocation, full flexibility

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((16, nl.par_dim(128), 512), ..., buffer=ncc.sbuf.alloc(...))

# Direct allocation, modulo allocation

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((16, nl.par_dim(128), 512), ..., buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(...))

The PSUM allocation APIs, ncc.psum.alloc() and ncc.psum.mod_alloc()

follow a highly similar design. For more information on the semantics of these APIs, check out

API reference page for allocation control.

ncc.sbuf.alloc()#

This SBUF allocation API enables user to control:

the number of physical tiles to allocate for a given NKI Tensor, and

the exact mapping between logical tile and physical tile in SBUF

ncc.sbuf.alloc() accepts a single input parameter, func, which is a user-defined callable object

that takes in:

a tuple of integers

idxrepresenting a logical block index,an integer

pdim_sizefor the number of partitions the logical tile has, andan integer

fdim_sizefor the number of bytes the logical tile has per partition.

The func returns a tuple of two integers, (start_partition, byte_addr), representing the memory location

of the mapped physical tile for the given logical block. start_partition indicates the starting partition of

physical tile and must follow these ISA rules:

If

64 < pdim_size <= 128,start_partitionmust be 0If

32 < pdim_size <= 64,start_partitionmust be 0 or 64If

0 < pdim_size <= 32,start_partitionmust be one of 0/32/64/96

The byte_addr indicates the byte offset into each partition the physical tile allocation starts from.

For example, on NeuronCore-v2, a valid byte_addr can be any integer values from 0 (inclusive) to

192KiB-16KiB=(192-16)*1024 (exclusive). 192KiB is the physical size of a SBUF partition

and 16KiB is allocated for compiler internal usage.

Refer to NeuronDevice Architecture Guide for the physical SBUF partition size

on each NeuronCore version.

In addition, byte_addr must be aligned to nki.language.constants.sbuf_min_align.

At compile time, the compiler will statically evaluate func over indices of all the

logical tiles defined in the NKI tensor to calculate physical addresses for each tile. As an

example, consider the following simple allocation that allocates four physical tiles back to back along the free

dimension of SBUF, with every logical tile mapped to a different physical tile sequentially.

def simple_1d_alloc_func(idx, pdim_size, fdim_size):

idx, = idx # unpack the tuple

return (0, idx * fdim_size)

t = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.alloc(simple_1d_alloc_func))

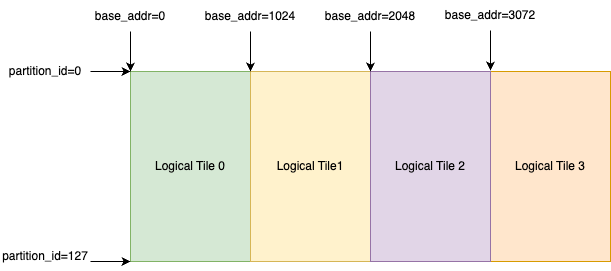

In this example, the compiler will query simple_1d_alloc_func with idx ranging from (0, ) to (3, ),

pdim_size=128, and fdim_size=512*sizeof(nl.bfloat16)=1024. We can visualize the final allocation in

Fig. 77.

Fig. 77 Visualization of simple_1d_alloc_func in SBUF.#

This ncc.sbuf.alloc API provides great flexibility through the customizable function to perform

logical to physical tile mapping. With Python closures, the function can carry arbitrary metadata,

which enables programmers to define their own memory allocator. As another example, here’s a simple

allocator that queries a global variable next_addr to keep track of the next available byte address

in the free dimension.

next_addr = 0

def simple_1d_alloc_factory(total_fdim_size):

base_addr = next_addr

next_addr += total_fdim_size

def simple_1d_alloc_func(idx, pdim_size, fdim_size):

# unpack the tuple

idx, = idx

# hard-code to partition 0, since each tile takes up 128 partitions

start_partition = 0

return (start_partition, base_addr + idx * fdim_size)

return simple_1d_alloc_func

# Using simple_1d_alloc_factory, next_addr is automatically incremented.

# Physical tiles of t0 and t1 start at 0 and 4096, respectively

t0 = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.alloc(simple_1d_alloc_factory(512*2*4)))

t1 = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.alloc(simple_1d_alloc_factory(512*2*4)))

ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc()#

Alternative to the ncc.sbuf.alloc() API which requires programmers to define an allocation algorithm

from scratch, NKI also provides the ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc() API which invokes a pre-defined

modulo allocation scheme in Neuron Compiler.

Modulo allocation works as follows. Suppose that we allocate

two physical tiles for a tensor with a logical shape of (8, par_dim(128), 512). The eight logical tiles

are assigned to the two physical tiles by taking a modulo of two on the logical tile index (that is, block index).

Therefore, logical tiles with index (0, ), (2, ), (4, ), (6, ) share

the same physical tile, while logical tiles (1, ), (3, ), (5, ), (7, ) share

the other physical tile.

The ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc API takes four input parameters:

base_addrindicates the starting byte offset within each SBUF partition of the physical tiles.base_partitionindicates the starting SBUF partition of the physical tiles.num_par_tilesindicates the number of physical tiles to be allocated along the partition dimension of SBUF. This is only applicable for tiles that use fewer than 64 partitions per ISA constraints.num_free_tilesindicates the number of physical tiles to be allocated along the free dimension of SBUF.

Given the above input parameters and the modulo allocation scheme, Neuron Compiler is then able to calculate

the physical tile memory location, (start_partition, byte_addr) for each logical tile in the tensor.

Note, this is the same information that the callable allocation function passed into ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc()

would return. See API reference manual for ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc

for the exact formula to calculate (start_partition, base_addr).

Next, we discuss a common use case of ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc, which specifies only

the base_addr and num_free_tiles fields while leaving the remaining parameters to default

(base_partition=0 and num_par_tiles=(1,)) .

nki_tensor = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(base_addr=0, num_free_tiles=(2, )))

This produces the following allocation:

Logical Tile Index |

Physical Tile |

Physical Tile |

|---|---|---|

(0, ) |

0 |

0 + (0 % 2) * 512 * sizeof(nl.bfloat16) = 0 |

(1, ) |

0 |

0 + (1 % 2) * 512 * sizeof(nl.bfloat16) = 1024 |

(2, ) |

0 |

0 + (2 % 2) * 512 * sizeof(nl.bfloat16) = 0 |

(3, ) |

0 |

0 + (3 % 2) * 512 * sizeof(nl.bfloat16) = 1024 |

The above example is an easy way to implement double buffering without having to define a callable function

manually like how we did for ncc.sbuf.alloc(). We can also implement multi-buffering

using ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc() by changing the value of num_free_tiles (or num_par_tiles

when each tile occupies less than 64 partitions).

Development Best Practices#

First and foremost, direct allocation APIs are considered advanced NKI features for performance optimizations.

We highly recommend using direct allocation API only after your kernel is functionally correct with automatic allocation.

Automatic allocation is invoked when NKI tensors are declared with buffer=nl.sbuf (alias of ncc.sbuf.auto_alloc)

or buffer=nl.psum (alias of buffer=ncc.psum.auto_alloc).

The rest of this section goes over best practices of direct allocation APIs to optimize kernel performance.

#1. Hoist allocations outside of the loop-nests you want to block across#

To parallelize a loop, every tensor used in the loop must have

multiple live tiles so that the different hardware engines can read/write from/to different memory locations

in parallel.

To achieve this, make sure to allocate tensors with logical block dimensions above any loop

you want to run in parallel. For example, the following loop will be serialized because t has only one tile alive,

for i in affine_range(8):

t = nl.ndarray((128, 512), dtype=..., buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(base_addr=0))

t[i] = ...

# do something with t

To improve parallelism, programmers should hoist the tensor declaration and allocation above the loop, like this:

t = nl.ndarray((8, 128, 512), dtype=...,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(base_addr=0, num_free_tiles=(8,))

for i in affine_range(8):

t[i] = ...

# do something with t

#2. Avoid PSUM Bank Collisions#

As discussed in NeuronDevice Architecture Guide, PSUM in each NeuronCore has eight banks that can accumulate TensorE matrix multiplication results independently. Especially in complex loops where PSUM tensors have multiple logical block dimensions, programmers should pay close attention to PSUM bank allocations so that they do not collide.

More examples coming soon.

Common Errors#

This section goes over the common compilation error programmers may encounter while using direction allocation APIs.

#1. Mixing direct allocation with automatic allocation.#

Automatically allocated tensors from default arguments or lowering need to be explicitly passed to those NKI APIs or their allocations will collide. When direct allocation is used, all tensors, including the tensor returned from a instruction, in that kernel must also use direct allocation. For example,

t = nl.load(input) # t is a new tensor, this will fail

# the correct way

t = nl.ndarray(shape=..., buffer=ncc.sbuf.alloc(...))

t[...] = nl.load(input)

#2. Calling compute APIs that introduce implicit tensors while direction allocation is used.#

Certain NKI compute APIs implicitly create constant or intermediate tensors that are not

in programmers’ control. For example, invoking nisa.nc_transpose

with engine=nisa.tensor_engine

creates an identity matrix under the hood, which cannot be allocated explicitly using direct allocation APIs.

Similarly, many high-level nki.language APIs, such as nl.softmax <api/generated/nki.language.softmax>,

are lowered down to several nisa APIs

in the compiler. The intermediate tensors between these lowered nisa APIs also cannot be explicitly allocated

by NKI programmers.

Therefore, due to restrictions discussed in common error #1, such APIs are not allowed when direction allocation is used in the kernel. A compiler error would occur when this is violated.

#3. Lifetime Conflicts#

Each NKI kernel has its own address space, and any physical tiles that must be alive simultaneously due to compute definitions of the kernel should be assigned unique addresses in the kernel address space. For example, tensors below have partially overlapping physical memory addresses, which would cause errors if the two tensors need to be alive at the same time.

# t0 physical tiles occupy:

# partition [0:128],

# byte_addr [0:512*num_free_tiles*sizeof(nl.bfloat16)] = [0:2048]

t0 = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(base_addr=0, num_free_tiles=(2, )))

# t1 physical tiles occupy:

# partition dim - [0:128],

# free dim (byte_addr) - [1024:1024+512*num_free_tiles*sizeof(nl.bfloat16)] = [1024:3072]

t1 = nl.ndarray((4, par_dim(128), 512), dtype=nl.bfloat16,

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(base_addr=1024, num_free_tiles=(2, )))

Another common lifetime conflict error is when the number of physical tiles is insufficient to hold all the logical tiles that need to be alive at the same time. For example,

# Lifetime conflict #

t1 = nl.ndarray((8, par_dim(128), 512),

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(byte_addr=0, num_free_tiles=(2, )))

for i in nl.affine_range(8):

t1[i] = nl.load(...)

# End of loop: we need all eight logical tiles in t1 to be

# alive in SBUF so that we can start the next loop.

# Only two tiles can be alive according to our allocation above -> ERROR

for i in nl.affine_range(8):

result[i] = nl.exp(t1[i])

##############

# Correct way #

for i in nl.affine_range(4):

t1 = nl.ndarray((2, par_dim(128), 512),

buffer=ncc.sbuf.mod_alloc(byte_addr=0, num_free_tiles=(2, )))

for i in nl.affine_range(2):

t1[i] = nl.load(...).

result[i] = nl.exp(t1[i]) # t[i] are dead after iteration, thus no error

Neuron Compiler has built-in checks for such lifetime conflicts. For example, when there is a

PSUM tensor lifetime conflict, an error like “[SCH713] Violation of accumulation group interleaving”

will be thrown. However, the lifetime checks in

the current release are in-complete, which may not catch all the lifetime violations in the kernel.

If the kernel using direction allocation API generates incorrect results numerically, one plausible cause is

the kernel has tensor lifetime conflicts that are not caught during compilation. One way to verify this is to

re-compile the same kernel with automatic allocation forced on using the force_auto_alloc decorator.

Known Limitations#

When direct allocation API is used, HBM tensors cannot be declared unless they are used as kernel outputs.

All tensors declared with

buffer=nl.shared_hbmmust be returned as the result of the kernel.Tensors declared with

buffer=nl.hbmorbuffer=nl.private_hbmare not allowed.A compilation error

Non IO HBM tensor is not supported in allocated NKI kernel: <list of tensor names>will be thrown when such a tensor is encountered.

For

ncc.psum.mod_alloc, thebase_addrandstart_partitioninput fields must be 0. This implies that only one physical tile can live in a PSUM bank at a time and the PSUM tile must start from partition 0.A PSUM tile cannot cross bank boundaries. Therefore, the size of the free dimension of each tile has a maximum of 2KiB, or 512 FP32 elements.

The compiler’s ability to check for race condition and lifetime conflicts is limited. It is not guaranteed to catch all race conditions.